CARLES CONGOST

La Mala Pintura

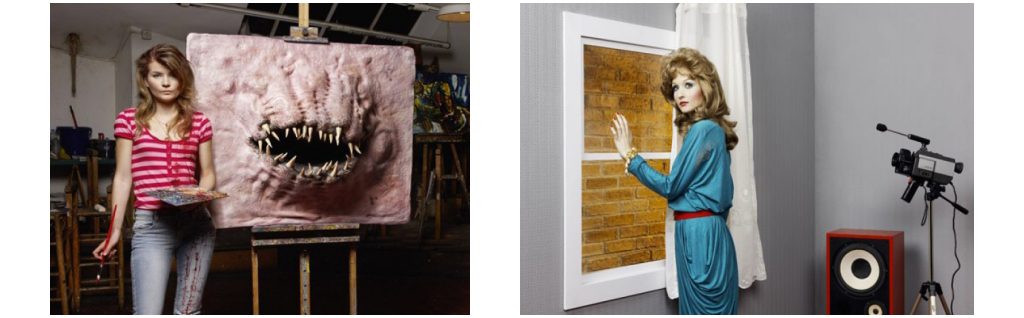

Carles Congost, Mr. Ryan Paris As The Famous Italian Curator, 2008 – C print on aluminum bond, 40 x 59 inch

.

OPENING: Saturday, 21 June 2008 – h 6.00 pm

31 June 2008 – 30 September 2008

.

Text by LUIGI MENEGHELLI

The Spaniard Carles Congost is an omnivorous artist who accumulates and devours languages, themes, and figures, who manipulates genres, traditions, and allusions with an indiscriminate imagination for combinations. His vision collects everything together: Ballard and X-Files, Tarantino and Captain Marvel comics, Cronenberg and Romero, all in order to recount the ambiguity of what surrounds us and to discover the unmentionable dark areas behind reassuring social norms. It is enough to refer to the video (2003 and previously shown in this gallery) titled Tonight’s the Night where, behind the blatant conformism of a bourgeois family, there lurks an impending and mysterious mutation (of the body, age, spaces) or Spaceboy, again dating from 2003, which presents a person who, more than experiencing history, experiences a state of mind, a journey towards the loss of himself, emptiness, and death.

And yet Congost’s video art (and also his installations, photographs, drawings, and music) is not intended to produce a moralistic discourse, to shine a light onto prohibited acts or to penetrate the unnameable ecstasy of evil, but to propose the normal, the obvious, the evident but in another guise: probable nightmares, fakes without any possibility of being unmasked. He wants to project his vision beyond what it is given us to see. So the narrative is never a process, a progress, a precise trajectory but a chase after infinite perspectives, erratic trajectories. It is never linear or panoramic: it has no format but seems about to shoot out in every direction, as happens in a series of video clips. His aim, he says, is to offer a new perspective on the world by widening out an incomplete, imperfect portion of reality.

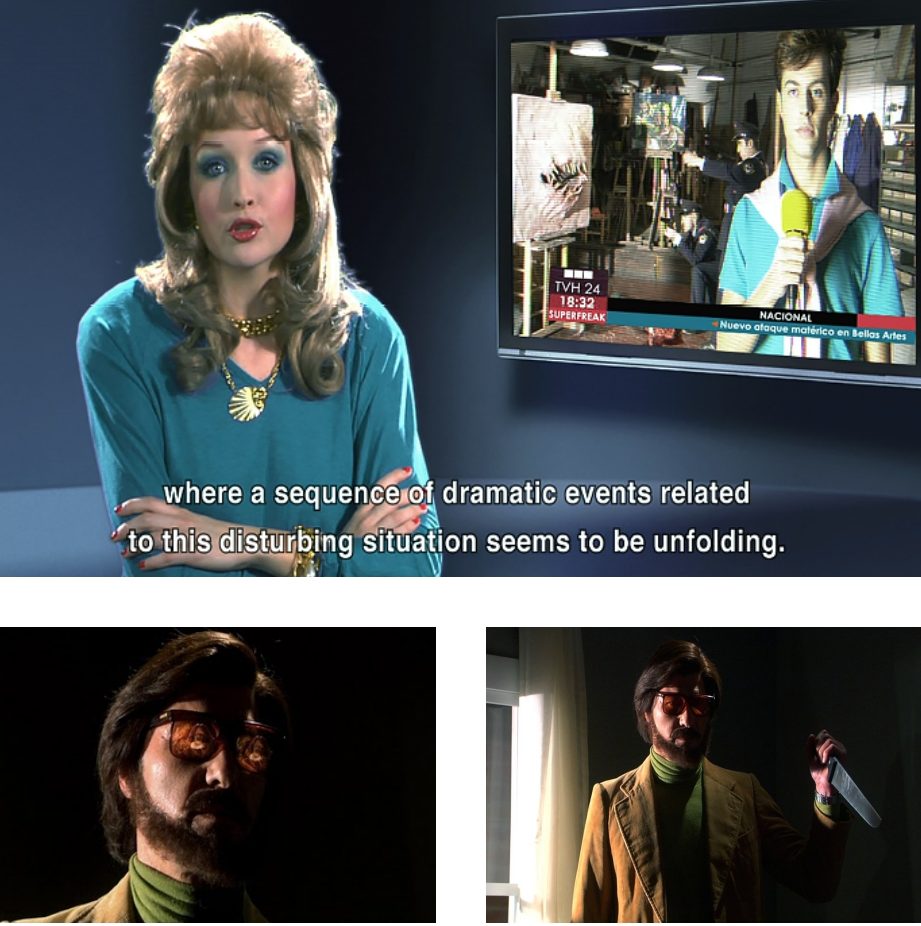

But what if this very narrative were a “mask”, a sublime fraud? What if events that give the impression of continually chasing themselves among temporal and spatial rejects were nothing other than time as it is, an image that is more than an image, time that is contained many times in itself, a journey that happens within the image without any need of being simulated during the editing or the action? This, in fact, is what seems to be suggested the tremendous video by Congost La Mala Pintura. This journey to hell by a shady curator (preceded by the seductive phrase “A few months ago”) does not refer to a real time shift but to a pure artifice typical of film language, just as the materialisation of the three genies of the “Siglo de Oro” (Murillo, Velasquez, Zurbar‡n) does not allude to a return from the abyss of history of three famous masters of art, but to “monsters” who spring from within, ghosts who are the subjective emanations of the curator. The problem lies within the comparison between the past and the present, between painting tradition and new IT languages, between images bonded to the roundedness of their body and immaterial, light, transparent images. This is a consistent dialogue in which the authority of history seems to have won, destroying calendar time and suggesting itself as the eternal source of knowledge. But then, as though in a mirage or a dream, the image returns to revolve spirally around itself, almost as though to circulate around the very meaning of its being. In fact we must not forget that Congost questions himself about the “physiognomy” of art and its way of displaying itself: for instance, in the video That’s my Impression, 2001, a contemporary art expert tries to analyse the work of the artist in a theoretical way which inexorably shows itself to be unsuitable to any kind of real understanding; Memorias de Arcaran, 2005, narrates the story of an invented town inhabited by artists which, however, reflects on their social role and the relationship between art and power. In La Mala Pinctura Congost places in the forefront the concrete sources of art: its systems, its history, its tools, its venues. He even arrives at showing the problem of the “aura” raised by Walter Benjamin in his famous essay of 1936, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility”. And he does by way of a young artist (probably his own alter-ego) who reads various extracts from the text to the very curator who is ready to kill in the name of “traditional Spanish values”. The scope is that of contrasting art characterised by the sacred values of art, by its aspect of a place for a revelation of the absolute, with the value of exhibition (in the age of its technical reproducibility), because of which art becomes pure communication, a mass social event… At this point it will have been understood that La Mala Pinctura is a video brimming over with subjects, references, quotations (even quotations of quotations). It can be said without fear of contradiction that the various passages, mutations, and alternations are all to be found within the images themselves, they are part of their narrative structure. And yet, if we think about it, there also emerge subtle fractures, dislocations, duplications (and re-mirroring) rather as happens in the crazy fragments generated by the splintering of a sphere in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane: they are genuine slices of vision (or in vision), but Congost hurries to join them back together again through the symbolic use of dark glasses with their capacity to create mysterious fascination, and through the vertigo of relationships based on appearance: the hypnotic sphinx effect. And given that it is the sinister curator who wears the shades, on the one hand they hide his gaze and “close” his face, on the other they are superimposed over his vision and become the screen for distressing and hellish projections which are nothing other than his “second” sight, the more intimate one, that of his dark and damned soul. But the whole video continues to propose effects of substitution, radical illusions, obvious deceptions. In La Mala Pinctura there is a superabundance of morphing, of open mutations, of old re-varnished tricks palmed off as new (effects of effects): starting from the anachronistic clothing of the protagonists, their overdone makeup, the operetta-like scenery to arrive at “Grand Guignol” images with obscene and voracious worms, and paintings that change into disgusting and murderous beasts, as in the films by Roger Corman. Congost certainly has no fear of trash: on the contrary, he pushes down the accelerator and goes far beyond the obvious allusions to American spy stories or Bcertificate cinema noir. He is in search of the incongruous, of an absolute visual confusion, the aesthetics of “as if”. He makes use only of salvaged material derived from the most varied sources and stimuli (television, cinema, comics, advertising): what is important is that they be both elevated yet degraded, cultural and lowbrow, noble and sloppy (out of place). It is like this from the very opening sequence which ridicules videogames; but he also does so with the television news which interrupts normal TV transmissions in order to link up with the school of fine arts where dramatic things are happening: the tone is that used for great and sudden disasters, but here the television camera (a video within a video?) only frames two disreputable policemen who are firing pellet guns against the appalling beast. And this is also how it is with the blood squirted in the face of a student who almost laughs, as though she were a model for Yves Klein ready to become a work of art; and above all this is how it is with the song “I’m alive!” sung while the final credits roll, together with the figure of Ryan Paris, a name as fake as a counterfeit perfume. It’s true: Congost stockpiles elements derived from the most heterogeneous streams of mass sculpture, but he operates on them with a kind of narrative (and perhaps even ethical) short-circuit that turns them into a trick, a quip, a joke. If it might seem that everything occurs between subtle games of winks and nudges towards mass media materials, there is no affirmation of belonging or relationship with them. On the contrary, the artist himself reveals that his aim is that of bringing about a kind of subversion of usual communicative codes. Where, in fact, is the distinction between reality and unreality, ordinariness and excess, convention and critical-ironic detachment? Once more it is Congost himself who is forced to admit “I know what it (the video) is not, but how can I explain what it actually is?”. All orders of reality are here mixed together, as though in the crime film by Bryan Singer, The Usual Suspects, where the whole story turns out in the end to be the projection of the protagonist’s lie and where good and evil change places. In the La Mala Pinctura too it is the young man using MySpace who captures the presumed murderer on his monitor and then wipes the image out. As though to say: hyper-pretence; or, in other words, what you see has never existed not even at the level of fiction. But then Congost has spoken of a frantic use of “theatricality”. He has said, “Each sequence in the video has a different formal resolution according to the nature of what I needed to tell. Thus, I built fake sceneries, I used digital backgrounds and I also shot in real locations”. His is a vertiginous effect of redoubling and metamorphosis. And it is as though he answers in a homeopathic way to these three disquieting masters of the Baroque by comparing their own words exalting the Golden Age with a similarly Baroque overflowing of forms, travesties, and diversions. There are also exhibited in the show various photos derived from videos or taken during the shooting, and even photos taken of backstage events. “The idea is to offer an extension of the video” to extend its capricious yet hilarious brutality but, above all, to show what normally escapes from sight (such as the mass media devices within the video): in other words, what is unseen because of the too-speedy passing of the photo frames or what is rejected and thus hidden. It is a vision that unmasks (or frees?) what, once again, remains trapped inside (or behind) history. A reject, then, that is to be understood not as a lost form, as a privation, but as an object (an image) that is precious because it captures and puts into focus the fundamental, topical “faces” of the process. A reject as an element of diversity which brings about, within what is known, a sense of rarity, of an “iconic” value.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Carles Congost, Walter & the Spanish Baroque Gang in The New Golden Age, 2008 – C print on alluminium d-bond, 31 x 53 cm

(DESTRA) Carles Congost, Bad Painting, 2008 – C print on alluminium d-bond, 44 x 47 cm / (SINISTRA) Carles Congost, Rapture (American Remake) 2008 – C print on alluminium d-bond, 38 x 55 cm

Carles Congost, La Mala Pintura, 2008 – Video, 20 Minutes